QUOKKAS SHARPED OUR CARDS

There’s a junk shop across the road from where we’re filling up the Chook. We go in wondering about various things. I’m wondering about knives.

I get a little lost while browsing. I’m six or seven years old and I’ve just pilfered my father’s pen-knife from a slim wooden drawer in his desk. I bring it to the downstairs bathroom, a safe place that accumulates warmth from a radiator no one knows how to shut off. I take off my pants and sit on the toilet. I don’t have to go, but it feels unnatural to sit on the toilet with pants on. I test the sharpness of the pen-knife blade.

My mother finds me, a few minutes later, bawling and bloody. She sees my pants around my ankles and concludes that I have attempted a second circumcision. It is difficult for me to get across, while bawling, that no, I only cut my finger, my pants are around his ankles only because

I give up searching for the scar on my finger and apply myself to articulating to the shopkeeper, who has a face like braided bread, what it is I want from a knife. I’m looking for a folding knife. Something simple. I might have one left, the shopkeeper says. He goes behind the counter at the front of the shop and finds a knife for me. It’s not inside any cabinet, but on the floor.

Last one. I had about two dozen of them, beautiful knives. Someone came in and bought them all. Don’t know what one man could want with so many knives.

I don’t either. It seems like something a cult would do: buy dozens of matching knives.

The knife is everything I’d hoped for: sturdy, uncomplicated, and sharp. The handle reads “King Fish.” I ask the man how much he wants for the knife, and I’m surprised to find it costs about as much as a candy bar.

L has found a pair of sturdy plastic cups; she and I have been drinking wine out of a shared coffee mug lately, and while browsing in the junk she must have experienced an impulse to civilize our dinners. The cups are marked three dollars each, but the shopkeeper says she can pay two AUD for the pair. She seems puzzled. Then she says she’ll tip him the difference.

Is this where tips go? she asks, regarding a plain wooden box with a slot in its lid. Try it and see, the shopkeeper twinkles. At the entrance of the coin, the box collapses in on itself with enough force to kill a mouse. L jumps back. The shopkeeper’s laughter reminds me of a struggling engine.

***

Among the campsites in the tingle grove a single cabin looks down from a steep dirt drive. Rainwater collects in a tank beside it. There’s a plaque on the door that reads “771,” as though there were 770 other cabins besides this one. There is only this one.

We claim this cabin for our shelter. Those claimants who came before us have left behind on the wall beams small reliquaries of snapshots and drawings. The place inspired them. The floorboards are bare and too heavy to creak.

It is the woodstove that makes us gasp and question why the universe should favor us so. The woodstove squats in the corner like a well-fed dog.

We go to gather firewood before darkness falls, but find not much that’s dry. Some of the wood is already scorched, presumably by bushfires. Lacking an ax, we wedge long branches under the cabin to break them into manageable logs. L tries putting a log under the wheel of the Chook and driving over it. It doesn’t work. We laugh.

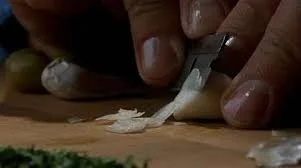

She builds our fire in the woodstove while outside, over a campfire, I cook a mixture of rice, canned tuna, tomato, onions, and garlic. With my new knife I cut paper-thin slices of garlic and think about Paulie from Goodfellas.

With our meal we drink wine out of the cups L bought. We light candles and play poker with pistachio shells for chips. Neither of us care about the chips that fall through the slats of the picnic table.

Other campers have come to inhabit the dark dirt lots down the hill. They all arrive in the blue hours when the flies have grown subdued and the kookaburras are calling on the night. They come up the hill with empty water vessels and come down the hill with full water vessels and jealousy tickling their throats. I hear a baby crying, a baby which implies a family, a family which would surely appreciate the comforts of Cabin 771. This is not a story of our virtue and our generosity. The kookaburras are laughing. Probably at all of us.

Our neighbors come for water, but can’t leave without betraying their true motives. A white Australian lady with dreadlocks wants to know how we found this place; only locals used to know about it. A road-fried Frenchman wants to have a look inside the cabin. Just to see what he’s missing. I think about telling him that our baby is sleeping in there, but I don’t like to implicate L in my fictions. We have no baby.

We let him have a look inside and he tells us he finds it creepy in there. I don’t know what he’s talking about until I get up in the middle of the night to urinate and look back at the cabin where the firelight inside has gone pale at the windows and flashes like an electrocution in progress. But that’s only from the outside. Inside, our woodstove throws over us a night-warmth we have not experienced for weeks, not since Melbourne. Before we sleep we agree to stay another night in Cabin 771.

By morning all the neighbors I can see from the vantage of the cabin have cleared out. I’m up before L. We left the cards in a neat pile on the picnic table; now they’re scattered, some on the ground. I pick them up, and as I count them find some damage. The edges of five cards have been ground down, as if by a blade. Sharped.

It takes a lot not to wake L and show her. Over breakfast she convinces me it wasn’t our neighbors who came in the night and messed with our cards. It was probably quokkas. Animals nibble at cardboard sometimes.

Jack of hearts, king of diamonds, queen of clubs, two of diamonds, five of diamonds. Not much of a poker hand. Wouldn’t beat Hickock’s.

We return from a walk to find a fine dust of ash has settled on the windows of the Chook. We look to the canopy and find more ash snowing down. How far the ash of a bushfire may travel on the wind is not something we know.

We get in the Chook and scan the local stations for news, but nothing’s coming through. I hear my voice go cold and toneless. We should pack up. If the ash keeps falling, we’ll drive out to where we can hear the radio. Our car will be packed, and we’ll be able to decide which direction to drive and whether staying another night’s a good idea. The ash keeps falling.