CASUALTIES OF AUSTRALIAN CINEMA

Wayne Gilroy had tried a few times before to distance himself from the biker pictures that earned him his place in the history of Australian Cinema; Another Round, Olly would be his last attempt. The story concerned itself with a pub owner, the titular Olly, quietly going sober. Wayne Gilroy had co-written the script and called in several favors to assure funding. And though the film dispensed with tire smoke and engines screaming at an earsplitting pitch, there would be action, at least a bit: bar glasses would fly, chairs would be smashed, yes, a bar fight in the first act would inject the otherwise intimate story (“toothless” in the assessment of one producer) with at least some of the sort of thrills audiences had come to expect from a film bearing Wayne Gilroy’s name.

The fight scene was never filmed. The blame for this lies mostly on a defunct cigarette machine. The machine provided exactly the sort of local color Wayne Gilroy was looking for in a pub location — it is featured in several scenes, including one where Olly’s love interest leans against it suggestively — but, in the case of the fight scene, the camera operator needed to set up a crucial shot in the corner occupied by the cigarette machine, and this meant removal.

Not until after lunch did anyone lift a finger to get the thing done. The first attempt went forward with the help of several patrons of the pub, who had assembled on this day, as they had all week, to drink and play extras and otherwise insert themselves into the production as they saw fit. A grip and three extras succeeded in lifting the machine, but the going proved slow. The extras, as it turned out, were more interested in making elaborate complaints than anything else. Talk soon turned to dollies, prising bars, and how exactly they would get the machine out the door if they got it that far. Wayne Gilroy overheard most of this, and it only confirmed something he had already suspected: that he might today need to involve himself in work that was not, strictly speaking, in a director’s job description. It wasn’t the first time. He had done some stunt work in the early films. Nothing outrageous, but he’d been riding motorcycles since he could tie his shoes, and sometimes it was easier to suit up and get on with things than to hire a stuntman for the day. His girlfriends got a kick out of it when he pointed out the shots where it was him under the leathers and helmet.

Rarely do people under physical strain have the presence of mind to listen carefully or converse in all but the simplest terms. There is some debate over whether Wayne Gilroy said anything when he stepped in to join the men struggling with the bulky machine; if he did, the men were too distracted to hear it. Wayne Gilroy found a handhold where he could and expected to make a difference: that much is confirmed. And it did seem, at first, that he had contributed, that he had lightened the burden on the other men; they brought the machine successfully out of the dusty corner, past the bar itself, and across the open floor, where they could have set the machine down, but strove on instead. Finally they reached the narrowest part of their journey, the doorway of the pub. There, while stepping backwards, the grip forgot there was a stair under his foot; he stumbled and lost his hold; this pitched the machine forward onto its front edge, where for a moment it teetered; Wayne Gilroy dropped his end, fell backward, and caught the full brunt of the machine coming down.

Pinned below the hips, Wayne Gilroy fought the pain by drinking schooners of beer and smoking cigarettes. With the beers he broke a sober streak just shy of four years. The irony of someone smoking cigarettes while trapped under a cigarette machine did not escape the eye of the set photographer, but this photograph has since been lost or destroyed.

From Wayne Gilroy’s demeanor — unsmiling, but also resigned and calm — all on set assumed he would make a full recovery once he was freed. But the specific geography of the bar’s entrance thwarted further efforts to move the machine; in falling on Wayne Gilroy, the machine had also become wedged in the doorway. Arguments broke out among the crew over whether an effort should be made to remove parts of the jamb. On the other hand, most of the extras found the director’s nonchalance contagious; they countered the alarmists on set with more rounds of beer for Wayne Gilroy.

It ended up taking almost an hour for an adequate prising bar and fulcrum to be found. By that time a great quantity of blood had pooled around Wayne Gilroy’s broken femur. He was looking paler and refusing glasses of beer.

The ride to the nearest hospital was ninety some-odd kilometers on dirt track. Behind the wheel was none other than the town doctor. He promised to take it slow, but not too slow. Wayne Gilroy and the doctor must have spoken along the way, for even if Wayne Gilroy was fading in and out of consciousness, the doctor knew many words of comfort, and knew by habit how to speak to people who were, for whatever reason, unable to lend him their full attention. The content of the conversation is known only to the two men and the lonely road. At some point past the halfway mark, the doctor reached over to Wayne Gilroy and discovered the man’s pulse no longer beat. He turned around and drove back to town, and when he was near enough to see the lights, he took a back road to bypass the pub, where Wayne Gilroy’s crew and would-be extras went on drinking late into the night.

No story is better fit for retelling in a pub than a story that itself occurred in the pub where it will be retold. Unlike many pub room tales, this one has a traceable source: it is the grip, the man responsible for tipping the cigarette machine over onto Wayne Gilroy. No man took the news of Wayne Gilroy’s death quite so hard as he. He never worked on another film, and while Cinema lost a dedicated operator, to call the grip a ‘casualty’ himself would be an insult to the memory of Wayne Gilroy.

After a while there was some talk of replacing the director and getting on with the production, but it was only talk; Another Round, Olly remains a collection of unfinished scraps from which no one has yet succeeded in reconstructing an intelligible narrative.

J got married in Montana in 2015. I piled into a Volvo station wagon with two other friends from high school and we drove there, from Brooklyn, in under 48 hours. It was my first major road trip and I didn’t know how to behave. Thankfully my friends are accepting people. I guess they were just as loopy as I was, owing to the speed and the sleeplessness of our journey. When I started speaking in an Australian accent, they encouraged me.

And even joined me. We babbled together about dingoes, kangaroos, hard country, and rabbit-proof fences. None of us had been to Australia. An Australian in the car probably would have shut us up in short order. Warned us we knew nothing of their culture, or just stared us down until we knocked it off. This hypothetical Australian would have had plenty of good reasons to stop our charade.

Slipping into an Australian voice was a childish thing to do; it would have offended or at least annoyed a broad cross section of people who existed outside of this particular car in these particular circumstances. Speculating as to why I chose to ignore my better judgment, and knowing that this sounds like a flimsy excuse, I will nevertheless contend that state borders were whizzing by so quickly the idea of borders became somewhat degraded. The borders of self seemed permeable. Why not try being Australian?

I experienced a bit of a hangover from that road trip. I found myself no longer wishing to impersonate Australians, even in receptive company. But I did not stop thinking about Australia.

Australia had become an idea. A wild land. Strange and lawless. I mean this in the most childish sense possible: my Australia in 2015 was a make-believe fantasyland. For exactly this reason it was very attractive. Even the vagueness of it — somewhere you could be someone else — carried a powerful allure.

I sought out some fiction about Australia. A part of me wished these sources — written or otherwise created by actual Australians — would temper my vague idea of Australia, maybe shape it in a somewhat more informed way. But if my aim was to know more of the “real Australia,” the fiction I consumed, both in literature and in cinema, did not really do the trick. It’s probably not the fiction’s fault. I read/saw what I wanted to read/see in these works. Illusions remained intact.

Under these circumstances I first came to the film Wake in Fright. Wake in Fright strikes most viewers as a good argument in favor of not going to Australia. A mild teacher from Sydney falls in with rough outback characters and spirals into depravity. He hits a low on a kangaroo hunt.

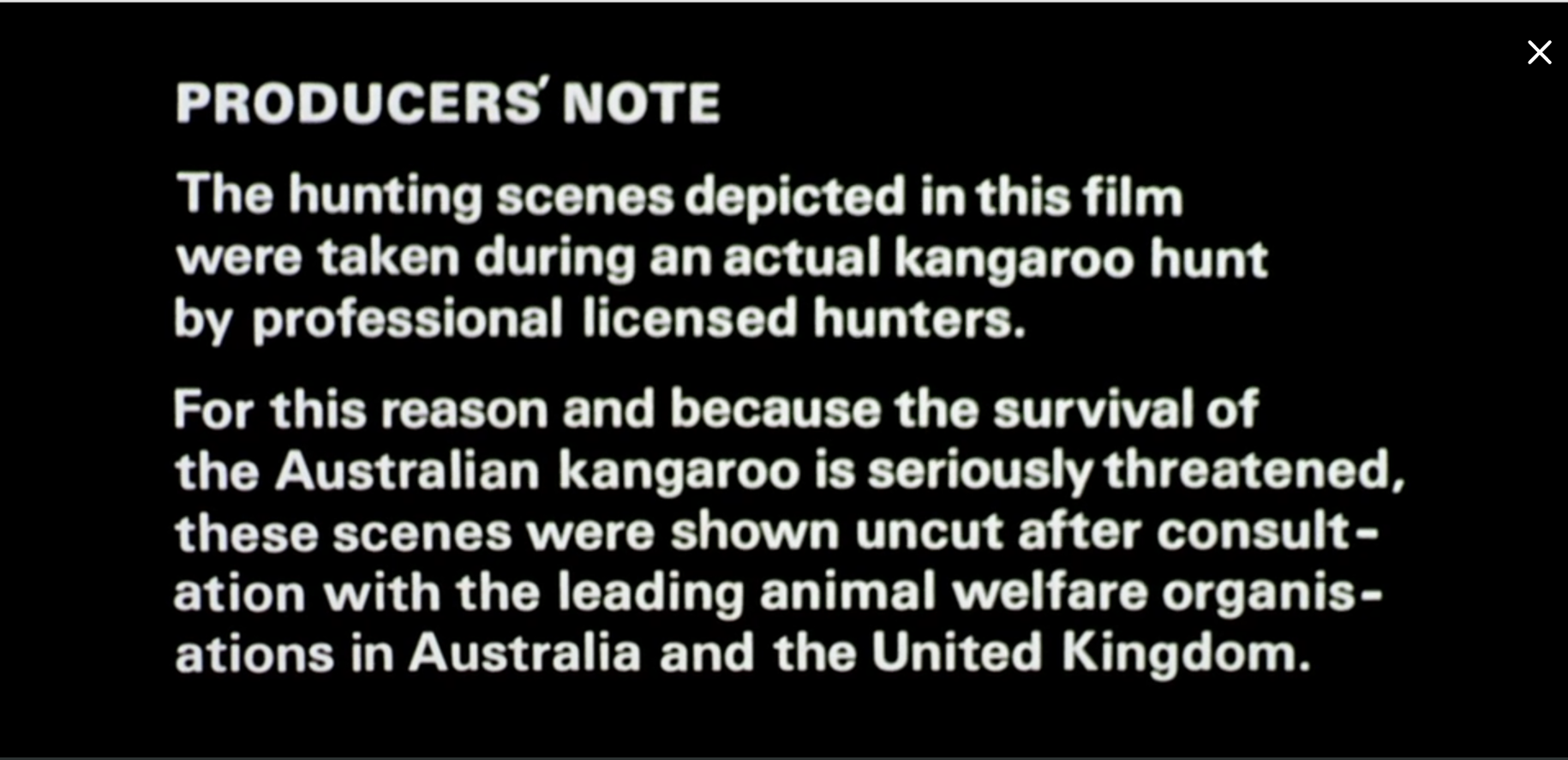

Kangaroos are actually killed in the making of this picture. The filmmakers rode along with kangaroo hunters to get the footage they needed to serve their narrative. It’s one of the most brutal films I’ve ever seen. But it did not put me off the idea of Australia. If anything, it reassured me that my fantasy could safely remain a fantasy. Wake in Fright could not be real. It had to be an exaggeration. No place could be so Australian.

Ladybug stood little chance of not loving horses. Her parents are cattle ranchers, not exactly horse people, but the horse was once essential to herding cattle, and horses are still put to work sometimes on this ranch. She has been riding and caring for horses all her life. She is a strong enough rider that her parents do not worry when she goes off into the bush for an afternoon. Towards the end of a muster, after the rest of us have rounded up the herd in utes, motorbikes, and a plane, Ladybug is permitted to come on her horse and drive the animals the last few kilometers.

Her father, the rancher, spends one morning on the phone trying to coordinate the sale of his horse. I don’t ask him directly why he’s selling this horse, but he feels the need to admit the reason. He breaks a light sweat as he explains that it’s the wrong horse for him, she’s too strong and too sensitive, she picks up on all his anxieties, and that’s a bad thing if you’re an anxious person.

Ladybug has overheard all this. The expression she trains on her father is unmistakably pitying.

If it’s a movie it should have a horse in it. Ladybug’s favorite is The Man from Snowy River; she admits this with some hesitation. Forty horses died in the making of it, she claims.

I don’t ask her how she can square the death of forty horses with entertainment. There is an answer in the mood that comes over her. Her eyes fall to the DVD boxes on the shelf. Then she goes off to see whether the chooks have been fed.

Her claim is not factual; one horse died in the sequel, but even that’s disputed. It’s a ripping good movie, though. There’s a scene where horse and rider careen down a rocky slope that must be forty-five degrees. They shoot it in slo-mo. Never mind that you can tell it’s a stunt rider: it’s stunning, eye-popping stuff.

It’s also the sort of thing that zaps the viewer out of the narrative; the slow-mo draws your attention to the fact that this is really a man on a horse flying down an impossible hill, never mind what sort of quest the man on the horse is involved in, right now we are watching a quest for survival, there’s a real horse and a real human at stake, we hope they both get down the hill in one piece. The action on screen is so flagrantly dangerous that I sympathize with Ladybug in assuming a great number of horses must have died in the making of this film.

An alienation effect is something Bertolt Brecht talked about in the context of theatre; it means a moment in a production, stage or screen, when the audience is made to feel aware of the production’s artifice and their role as a person in a chair watching it all. Theoreticians use the term to describe instances where the viewer is forcibly removed from the lull of viewing. This includes characters breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience. This includes showing a boom microphone in a shot, reminding us that there was filmmaking going on some time before the image reached us.

I would argue that the slow-motion shot of the horse on the hill in The Man From Snowy River fits the description of an alienation effect, but it’s probably not an intentional one, and I concede that the shot probably alienates me more than it does other people. If we’re being strict about terminology, it’s missing an important component. Brecht posited that alienation effects were best used to stimulate audiences, the better to wake them up to political/ideological messages present in a given story. Snowy River is pretty light on big ideas.

The footage of the kangaroo hunt in Wake in Fright hews more closely to what Brecht was talking about. It is alienating in the sense that it’s a departure from the previous aesthetic of the film; with long-lens photography and spotlights, it looks like documentary footage, because it is; the filmmakers shot it by tagging along with a crew of real kangaroo hunters. This is the disclaimer that plays right before the credits:

The “leading animal welfare organisations” agreed to the shooting and release of the footage in the hopes that we would all see just how brutal a thing it is to kill kangaroos. I come away from the movie with exactly that idea to mull over. And I don’t think the effect would have worked if not for the sense of displacement of the footage, the fact that it’s clearly documentary footage spliced into an otherwise elegantly shot feature, the fact that the kangaroos are really dying; the alienation of that experience keeps me wide awake.

I’ve now discussed two films where reality feels like an interruption. I want to linger on this idea a little longer, because I have experienced a mirrored effect in my life.

This life proceeds along with strict verisimilitude. The stovetop percolator heats against a blue flame, makes a sputtering roar, shoots a jet of steam through a vent; the handle is hot in my hand, and the coffee tastes about the same as it did yesterday. But, every so often, fantasy interrupts. In dreams. In stories that I read/watch/hear. In the active step of playacting an Australian voice.

The phrase “flights of fancy” seems apt, if outmoded, to describe these interruptions. I like that the word flight is involved. There is both the sense of escape and a high to what I felt, in 2015, when thoughts of Australia came to interrupt my life.

The thing is, you can’t really enter a film or enter most ideas. But you can enter Australia. My idea of Australia only existed in my imagination, but the country is actually there.

I possess evidence of my time in Australia, in the form of photographs, videos, and ticket stubs. I still have the handle of a fishing rod I snapped while reeling in a crocodile; I own a pair of Crocs soaked in the red dust of Western Australia. These artifacts assure me that I have been there; however, at the risk of sounding like a crazy person, they do not make the experience feel more real. I am writing this more than a year removed from Australia, and my memories about the place have about the same level of textural detail as a film about Australia. My mind has rendered the memory and the fictional representation with about the same fidelity. Which isn’t so surprising, but it does make me question those who put reality on a shelf too far above fiction. Kafka managed to write a zippy novel about America without having ever gone there, and though it’s been a while since I picked up that novel, I remember deriving considerable pleasure from his impression. I liked the naivety of it. I’ve considered getting a tattoo of an image from the novel, the Statue of Liberty holding a sword instead of a torch, but have decided against it for reasons of misinterpretation.

You might remember a song you heard in a dream and be thrown into a state of confusion over whether you, as the master of your own dreams, composed this song, or whether it was a real song, one that existed outside of dreams. And because you can’t quite remember the notes, only that the song had a certain rhythm or that there was a lyric about a car in one of the verses, you may never settle for yourself whether or not the song belongs to the real world or the dream world. Australia has brought on a comparable sensation. L has been good enough to point out, while I was in the process of composing these entries, points where my recollection peeled off from hers. This has been educational, but also expected, not just because of what I’ve observed about the quality and failings of memory but for the plain fact that my time in Australia sometimes appears to me as more fiction than fact. My Australian memories seem to hang out in the same repository as memories of films and dreams. But this begs the question as to why Australian memories seem fictional — why these memories and not others?

Here’s my theory: memories that are visually compelling, i.e. cinematic (notably different from routine memories) have a better chance of staying in my recollection. Cinematic memories are what my memory (a black box I understand very little, as it turns out) seems to favor. I found Australia to be a cinematic place. There’s light, speed, and color. It looks different than America. The rocks are weird. There are kangaroos.

In the mid-1990s the leader of Japanese death cult Aum Shinrikyo dispatched some trusted associates to Australia to purchase a sheep station and test sarin gas on sheep; the leader did this in preparation for using sarin gas on human beings. These cult members in hazmat suits, probably stained completely red with dust, filmed their cruel experiment and sent the footage back to their leader in Tokyo, who shed tears over the sheep as he would not shed tears over the victims of his attack on the subways. There are Western Australians who also claim they saw/heard/felt an unaccountable explosion in the desert; many believed that Aum Shinrikyo was testing a nuclear bomb they had acquired. The vastness of the desert was cover enough for these activities. And I point this out not just to mourn the sheep, casualties of a particular kind of Australian film, but to point out the cinematic essence that Australia in my experience possesses. We have villains of cartoonish proportions. We have wide open spaces. We have an explosion. We have tears. We have dust so red as to seem artificial.

I made coffee in my stovetop percolator every day in Australia, on various fires and stoves, but I remember very few of these instances. There was one time when it spilled.

In any given Australian pub there may be a guy who knows a stuntman who was in one of the Mad Max films. Especially if you go to Queensland. Previous to my arrival, I had thought of Australia as cinematic; while I was there, I sensed how the imagery was constructed. Even if I never met any stuntmen, I knew they were around.

Because I sometimes take it as a sign when I keep hearing about some character, I tried to write some fiction about Australian stuntmen, then it turned into something about Australian cinema generally, then it turned into a failure. At the time I was writing it, I was on neither side of the Australian screen, neither observer nor observed. Stuck in the middle.

Ultimately I whittled the piece down to just a title. I was going to call it “Casualties of Australian Cinema.” I still think the title has a ring to it, which is why I’ve used it here, to characterize a diary in which there are no literal casualties, but a figurative one. What is dead is not my fictional idea of Australia — which has proved hard to kill — but the person who dreamed that idea. He is no longer with us. I can never summon the same idea of Australia as I once could. There are too many memories in the way.

I sometimes experience the urge to do an Australian voice, so I can’t rule out a return to Oz at some point, nor can I rule out another attempt at Australian fiction, though I recognize both of these undertakings will lack the spark of complete naivety. It would be a far distance to travel, burning jet fuel I’m resolved to treat as a rarer quantity than before, for an experience less dreamlike than the first, a flimsy sequel set in the future, but I won’t ever really know until I go again, so maybe I will.

Probably I will. There are people I want to see again.

Found under the cigarette machine that crushed Wayne Gilroy were the following items: brown glass fragments, likely from a beer bottle; a scrap of paper with a telephone number since disconnected; the corpses of any number of flies; AUD $2.30 in coinage; and an unopened packet of Craven “A” cigarettes. None of these items carry about them the whiff of a curse, nor do they hint at any conspiracy of vengeance against the director, nor any hidden designs on the part of Australian Cinema. They are simple, everyday artifacts that no one in the pub can account for or claim to possess, though some of the patrons have attempted to fabricate histories. A smoker, despite the fact he smokes a different brand now, has claimed the pack of Craven “A” cigarettes once belonged to him.